Science

The furthest reaches of the mysteries surrounding some of the deep questions of life may be beyond our ken to answer at present but science is peeling back some of the outlying shrouds.

Why take a cue from the behaviour-pattern that is said to typify the Ostridge? We should consider all the new evidence that comes to light. Light arguably is shed on aspects of our belief systems by scientific discoveries. If so, what is their possible significance?

no wondering what it is all about,

in science?

Does every probability

Exist or only what we see?

There’s mystery!

We and our fellow-creatures

Are made of the stuff of distant stars,

That’s romance.

– Wendy Shutler

There are several scientists or former scientists who take the view that spirituality and an understanding of th human condition can be based on scientific findings. References to some of these teachers are on the ‘Links’ page of this website under both ‘Spiritual Matters’ and ‘Science’ but what exactly is the science that propels us in this direction; how certain is it? Truth – be it of the nature of the world, or Nirvana, outer space, or numbers etc – is rarely understood by gazing at equations or considering entities such as quarks or neutrons. They can carry someone originating a theory part of the way but fuller realisation can come in a ‘Eureka’ moment. It is rare that a new Big Idea finds instant universal acceptance or acclaim but it behoves us to keep an open mind about some of the thinking that has been going on by people who know their science. Hypotheses based on evidence may fall short of proofs as needed in a court room or a laboratory but may be allowable pro tem even if the jury is still out. Not all scientific experimentation or the conclusions drawn from it stack up but earnest, expert experiments to try to tease out deep meanings deserve an open-minded hearing.

What do the findings, or some of the findings, tell us about the significance of our beliefs?

Scientific Discovery over time has affected perceptions of man’s place in the scheme of things; we no longer assume that the physical universe assigns geographic space to heaven or hell – some of our remote ancestors thought of ‘Heaven’ as ‘below’ earth – or bend the knee at during thunder storms to Thor.

What recent findings in science may affect our perception of our place in the universe?

Below are some of the questions in this context:

- In what way if any are we connected to everything around us?

- Can there be communication perhaps at a distance ‘remotely’ between people and/or other entities? If so, by what means might it be conducted if not by language?

- is there a fundamental animating spirit in our biological make-up? If so, what might this animating spirit be?

- What kind of universe is it that we are in?

- If man is not the architect of himself, does this imply that there is another ‘architect’? If so, what deductions about ‘it’ does rigorous conjecture lead?

- We come from the stars; is our composition or consciousness different in kind from what is in the cosmos; if so why should this be the case?

- Do the recent revelations about the workings of the human body including its sub-atomic parts have a relevance to what and who we are and, if so, what is it?

- What do discoveries about the natural world have to tell us about ourselves?

- What Is the connection between consciousness and quantum physics?

- Can human biology be physically changed by human intention? If so, how?

Below are some of the questions in this context:

- In what way if any are we connected to everything around us?

- Can there be communication perhaps at a distance ‘remotely’ between people and/or other entities? If so, by what means might it be conducted if not by language?

- is there a fundamental animating spirit in our biological make-up? If so, what might this animating spirit be?

- What kind of universe is it that we are in?

- If man is not the architect of himself, does this imply that there is another ‘architect’? If so, what deductions about ‘it’ does rigorous conjecture lead?

- We come from the stars; is our composition or consciousness different in kind from what is in the cosmos; if so why should this be the case?

- Do the recent revelations about the workings of the human body including its sub-atomic parts have a relevance to what and who we are and, if so, what is it?

- What do discoveries about the natural world have to tell us about ourselves?

- What Is the connection between consciousness and quantum physics?

- Can human biology be physically changed by human intention? If so, how?

The Brain of Einstein

Einstein’s brain was preserved after his death in 1955, but this fact was not revealed until 1978.

Medicine

Review: Your Brain is Boss by Dr Lynda Shaw

Review: Rupert Sheldrake – Morphic Resonance

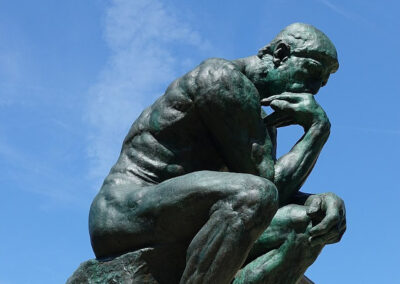

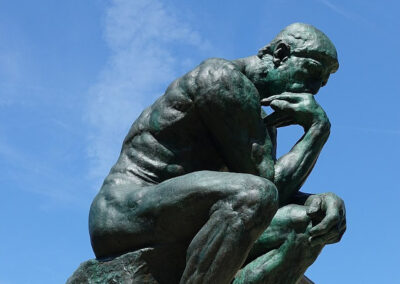

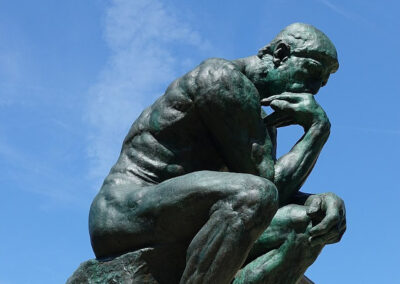

An example of intellectual reflection brought to bear on ruminative reflection

On Science

Remote Viewing Astral Travel

Supersolids and Entanglement

Some Science Based Theories That Should Have An Impact On Our Beliefs

How Ancient Wisdom Can Impact on Medicine

Artificial Intelligence

Biology and mind studies