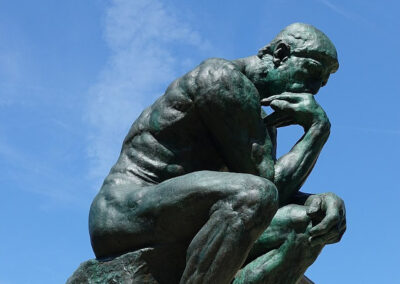

Practical Wisdom is the unseen front runner in the competitive stakes today to provide self-help advice. It is about self-realisation in action. The progenitor by the cradle of much of Western Civilisation, Aristotle, if watching, would no doubt give two cheers to see modern lifestyles. Top of the tree for Aristotle were three virtues: (a) Practical Wisdom (b) an understanding of how to live life well and ethically, and (c) technical wisdom.

It is sometimes assumed without much reflection that anything that smacks of a training for practical wisdom cannot be done other than in an ad hoc or piecemeal way. Wrong!

The ‘real’ world is in the forefront of our focus but not abstractions and challenges like ‘practical thinking for its’ own sake’. It is overlooked – out of mind because not commonly pointed out. If we want justifications for taking good practical decisions we look to the circumstances of a given case. It is much as if we are bent on treating symptoms, not causes.

Man is the only kind of varmint that sets its own trap, baits it, and then steps into it.

– John Steinbeck

A slight change in attitude – all it takes – to taking reflection more seriously is a key to practical progress. A start can be made in looking more closely into our fundamental thinking and creating habits of mind that are honed to the right approach.

There are signs of progress; reflection is coming into its own, with recognised beneficial effects but this is rarely put into so many words. Changes are gradual if apparently speeded up in ‘memory time’ than in day-by-day grappling with them. Adults know how perspectives taken for granted at the time apparently grow odder with the passing of years. There is almost an imperceptibility about the gradualness of change till a retrospective reckoning. There was an interview on TV in 2021 with the ‘sixties pop star, Donovan, in which he showed viewers the Ashram in India where he went with the Beatles for ….meditation. To that ‘fab’ group of hipsters it was an amazing thing to do, cocking a snook at the system, a form of revolution. To listeners hearing about it in the 21st century, it hardly seemed like a big deal. So it is with other ideas of Meditation that are gaining ground. Some 30 Peers from the House of Lords early in the millennium took three weeks out for a Retreat; the Tory Party of Iain Duncan-Smith organised a weekend for its top brass to spend time together ‘bonding’. Imagine their Victorian counterparts – clubbable as they were and in some ways more leisured – putting such a concept deliberately into practice as a recognised Activity.

A race is not always to the fleet of foot. Prayers have passages where ‘the calm quiet of the sabbath’ is seen as a part of achieving balance of mind, as well as communing with the infinite. The idea of ‘Reflection’ being treated as important in itself can help ameliorate a too-fast pace of life so as to allow more space for thinking. Many of us realise that something at times may be awry in our lifestyles from the way we rush from hither to yon, hardly with time for ourselves. It is not pre-ordained to be thus. The passing of a leisured lifestyle, for instance where the writing of letters with subsequent time taken for delivery, necessitating a passage of time, is just one of the ways that has made for a shift in how people see and live life. Contrariwise, patience is a habit is encouraged by the attention needed to fence for instance with quirks of computers. Recent lock-downs and home working have played a part in dampening down a too frenetic pace of life. People increasingly plead that ‘I want time for myself’. To some that sounds like a flimsy excuse; better can be the more persuasive ‘I need to find myself.’

The surprising thing is that we do not think more about practical wisdom per se given that it leads to where most of us want to go. We assume that we pick up on this key aspect of our lives wily-nilly or ‘on the job’. Wisdom played out in practical action, even downright common sense, is not taught in schools; it is not thought a viable subject. Who after all would make such a decision to include it in a curriculum, and what form could its implementation take? There are more courses for ‘self-help’ – almost a contradiction in terms – than ever, shrinks, gurus, life-coaches; studies galore tell us how to lead sensible lives but there is no central forum for discussion about what should be a central aspect of our lives, practical wisdom.

In most walks of life there is a grapple with how to train neophytes.

It is taken as read that we cannot transfer emotional memories to other people even if succeeding in this might help to bring about a valuable perspective on so many of the issues confronting us.

Reflection can be more of a habit, even a discipline, in its own right than in general is currently a norm so that it becomes second nature, and a trait that will stand one in good stead in many contexts.

COULD THERE BE A TRAINING FOR PRACTICAL WISDOM

Hard times create strong men, strong men create easy times. Easy times create weak men, weak men create difficult times.

– Sheikh Rashid

– Saying

– Emperor Augustus

– Bob Proctor

– Benjamin Casteillo

– Dostoyevski

***

Aristotle, teaching students in early adulthood, told them that if their parents had not already raised them to be virtuous, his lectures would not be able to help them.

‘Can wisdom or common sense be taught or enhanced?’ Does the answer call for a ‘Yes’ or a ‘No’, a common enough ‘all or nothing’ way of thinking? Common sense may be innate, wisdom acquired by learning the lessons of experience, but they can be enriched by training, as can most qualities.

The Israelites, handed down the tablets of stone with the Ten Commandments, moved on from Mount Sinai and no historically agreed spot marks the site. It is the only place in ancient Jewish history – it relates to a crux turning point in their fortunes – where no physical marker was put down. It was all too easy; it was just handed to them on a plate, so to speak. Easier by far to accept a verdict that is spoon-fed to one than struggle to acquire it for oneself.

Where is to be found the Boot Camp for Life designed to teach pupils to better adapt to face the snares and delusions of the world and more able to see things clearly, dispense practical wisdom, make wise and realistic decisions, understand where they may have been gulled?

It is easy see why people do not queue up to seek out unpleasantness even if they could learn valuable lessons from it. Featherbedding in a comfort zone has more charm. Feathers have a place within mattresses though not always in pillows.

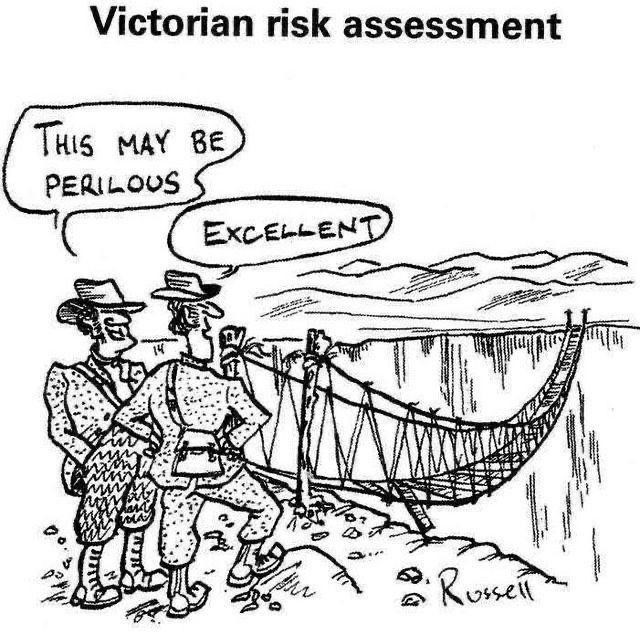

Commandoes undergo rigorous training to toughen up and so forth but…. what comparable training do politicians, or opinion-shapers or you and I undergo so as to better survive the School of Hard Knocks that is life? There is a very short list of successful experiments in suchlike social engineering. In Sparta or the Prussian military command or the English public school system, all passé in our cossetted era, hard realities consciously were factored into training. In ancient Rome, no soldier could play a full part in Vox Populi or even marry until his thirties and his military service was done. Fidel Castro before the Cuban revolution encamped in basic conditions in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Mao Zedong jailed by the Taichi’uts or during his Long March, Elizabeth I – persecuted by Lady Jane Grey amongst others – all had their teeth and wits sharpened by hardship. They learnt from it. But it was a part of their private journey in this Vale of Tears. Mao’s elite when he was in power had to spend a month a year in farms mucking out so as to instil in them such lessons. Mahatma Gandhi, on returning to his village in India, was tasked with cleaning latrines. It seemed to him that it was as important and difficult as diplomacy on the international stage. Some people are more aware of their debt owed to hardship. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had a drawer into which, on pieces of paper, he put the names of those who had tried to do him down. Those people gave him his most useful lessons in life, so he said. The principle is understood but not acted on as a point of training save in some rigorous specialist courses for professions. The title of UK TV’s ‘Boot Camp for Marriage’, not one to appeal to those who compare their betrothed to a Summer rose, is a nod in the direction of the principle.

The all-important advantages of suffering has been seen by the sections of the intelligentsia. The novelist, Saki, conjured up ‘Filboid Studge’, the tasty and nutritious foodstuff product at first not selling well despite its initial more enticing name. Sales took off when the Victorian British Public, taught sensibly to ‘Grin and bear it’, lapped up their opportunity to chew at the re-named horrid-sounding stuff between their Stiff Upper Lips. The unpleasantness was worth it; By Jove, it did them good. Flopsy bunnies, they were not! A ramrod back was the approved posture for an officer and a gentleman. The pill of Victorian education was soured, not sweetened by candy.

The concept of character-building seems outdated but there is purpose in building character that is not geared to outdated goals such as empire-building or martial adventure. What of the goal of monetary profit, etc? For all the business handbooks of instruction, a successful entrepreneur needs qualities of character including, often, nerves of steel. Are the tenets of religion fit for all contexts outside a church? Imagine a boss who did not want anyone upset. How often we hear about the three wise monkeys, who are said to ‘see, hear and speak no evil’. Is it true that a wise person sees no evil? The idea is not abroad that this is a charter for a naïvety.

An Ostridge gets no brownie points for hiding its head in the sand but it is not a bird that is commonly pilloried. We should foster the habit of testing what we hear with care The meek shall inherit the earth but the strong often seem to have got there first. A meek person is often the prey of a narcissist. They look for lonely people with low self esteem and who are also high on empathy. These people are often ‘reverse narcissists’, meaning, they grew up with the same pressures that tend to produce narcissism, but they chose the ‘better’ response, and became too empathetic, instead of not empathetic enough.

A rough ride has it’s uses as a training exercise, an experience attested globally and not just in the UK – an acid test of whether lessons are common to humanity, not just any one culture. ‘Endurance’ – Za Gaman in Japanese – is a TV gameshow where contestants have to endure humiliating and painful rituals. In Pentecost Island, Vanuatu, men jump off wooden towers around 20 to 30 meters high, with tree vines wrapped around their ankles.

There are practical reasons as well. Ancient Egyptian belles slept on pillows of stone to keep their hairdos standing tall. In some areas of the world the salutary principle is taken to the point of absurdity. Wilfred Thesiger, the explorer, recounted the story of a rite-of-passage ritual in North Africa where proof of manhood was killing a young man in an opposing tribe. Thesiger reported years later when revisiting the area that the tribes concerned had died out.

A toughening-up process can enhance appreciation of our lot in life. It can help graphically show how much worse off we might be than we are. The apple does not fall far from the tree. By maturity we may challenge their outgrowths but what of their roots? HOW can, or how CAN, we get our belief systems best adapted to our own times and our communities?

There are piecemeal experiments but at the moment of writing it is not a subject per se on which anyone with authority can act. No institute discusses it as a separate and worthwhile objective in itself. One can see why this is so; and yet good leaders are at a premium in societies, religions, schools and companies. No one is directing the process according to a system; it is left to chance.

Is the goal of an objective ‘Practical Philosophy of Life’ there to score? Could there be a prescription for a ‘School for life’ other than ‘learning on the job’?

One problem is that we are content to learn the lessons in life honed for the exigencies we face, not generally for those we do not face. Another question is: ‘what sort of character’? Much of what is said below will be common ground; it is known in general what are the best qualities to foster, from the time of schooling. It also helps to get our belief systems right.

Are we riding for a fall and, if so, can we do something about it? A ‘fall’ has happened over and over again in personal histories and world history, if with periods of respite. It is likely to go on happening till the tumbles that all but inexorably follow.

It is no good being spoon-fed. It is not easy in our non-reverential age to persuade people that they need ‘a taste of cold steel’. No one would listen to a pulpit-thumper of old:

‘O beautifully painted Humpty Dumpty in your hardened eggcup, O ye who think not of new paths, content to stroll in pastures of seeming green, the time is nigh to refresh thy ideas! O ye with thy licenses to wiseacre that ye sages and ye Gurus placard, enabling you are to coax or bully others with ‘your’ opinions – bullies who dance to the clarion of other Authorities and who, one fine day …will be coming for you!’

We do not have to adopt the style, be it cast in the pieties, homilies or platitudes of previous eras, or the old bugaboos starting with the fires of hell. There is plenty of scope on this earth to teach us how to live. Individuals all over the shop come forward with ‘improving’ ideas.

There have been attempts before to re-engineer education but a good starting point to fix problems might be to acknowledge what are the basic problems with more exactness, before trying to fix them piecemeal.

What of the lessons to be learned from history besides the facts of it? Lewis Namier almost single-handed changed the take on England’s history by concentrating on classes of people who had been almost air-brushed out of the reckoning; feminists now fillet history for hitherto under-acknowledged women of achievement. Our lens on the past changes with an eye to the future. Why leave it to axe-grinders to set the purposes when the idea is to get people objectively thinking aright. If we did that, women of achievement and the people who kept systems of society going would be treated automatically with the respect that they deserve. If, however, feminists are to rule the roost of education, why not consider more concerning the ways in which societies that do NOT treat womenfolk correctly disadvantage all their citizenry?

Then again, why just study military manuals devoted to the outstanding generals when a record and analysis of where and how the poorer sort of generalship lost out would be as condign a lesson? Why study just the military tactics of a Caesar or Clausewitz if military dunderheads furnish examples of what types of generalship to avoid?

Another sort of question, for example, is to ask is why Frederick the Great or Peter the Great were …not great. Why not study the lives of the known – and the relatively unknown – actors in history, not for their achievements so much as for their lifestyles?

Do whole countries fall prey to living in the mind-set of an earlier, preferred century? We should think about the sort of society, objectively, that will be in the interests of all of us, or as many as possible, in the future. What of the sort of character that is needed now?[1]

Much of what follows will be common ground, but perhaps not all. It is well understood how history has a big part to play in fashioning a perspective on the world. With religious teaching on the wane, morality teaching could be more upfront in taking its place. The experience of evil in the world comes of its own but the awareness of it being something to avoid should be a lesson imbibed with mothers’ milk. The morality lessons from history could be dinned more into impressionable heads. WW2, as remarked above, is an epic tale of revenge, with the ‘baddies’ gunned down in the finale. That idea could be cited more as a piece of human morality which goes to show – at a minimum – that crime does not pay. History abounds with examples of hubris come to grief. That conclusion could be spelled out in primary school textbooks. The ‘propaganda value’ of such books was understood by past generations. Our forebears promoted ‘Our Island Story’ which vaunted the glories of the British Empire. The committed of today have a very different agenda and it could be looked at in the interests of objectivity. The didactic ‘Single Issue’ tendency is intent on airbrushing out of the reckoning historical Greats like William Wilberforce. His campaign against slavery may not stim with political correctness. The Blame Game should apportion blame fairly; the reason that Rule Britannia has a line like ‘Britons Never Shall Be Slaves’ is because of an outcry against African slavers raiding the Cornish Coast.

As with morality lessons, so with emotional lessons. ‘Pride’, said to ‘go before a fall’, should be taught as a life lesson, with the hubris of narcissism distinguished sharply from a justified self-belief in an innate talent. That is but one example.

There is talk of sending poets into outer space. It’s not to get rid of them on a one-way ticket much as many a millennial might relish the prospect but so that people may better appreciate the significance of the enterprise and ‘significance’ of the right sort matters.

David Mercer, the playwright, once wrote that ‘the discerning pensioner can walk on Mars’. Empathy is human but it is regarded as confined to relations with living people in the present rather than having application to situations in general or with historical figures from the past. It is no wonder that TV, a medium treated as mainly for entertainment rather than education, is called the ‘gogglebox.’ The reality of what is seen on TV is not emotionally charged save to discerning people. A University professor was stuttering in shock on TV when telling of his research into the ‘second holocaust’, which had kept out of the history books by dint of secrecy cloaking Russian archives. The facts of how the Germans in a non-industrial way before the building of their gas ovens killed tens of thousands of innocents through shooting them down in cold blood struck him in force when he saw for himself the ravines of corpses, tangible evidence of what had gone on. There can hardly be anyone alive who has not seen the emaciated figures or corpses of the holocaust on ‘the box’. Born at a time when ‘9/11’ was treated by some as the epitome of human massacre, he seemed still not to have a full sense of the tragedy of WW2. Why not? The filmic evidence for instance on TV is clear.

An authorial voice is interposed: last night I had a nightmare. I woke at 5am convinced that I was in a room like a sort of gym where my role was to convince people by sweet-talking them into believing that the fate that they were about to endure was not grim, when it was. ‘I’ was doing this despite my basic wish to be honest with them because I was scared stiff of the Authority that was ordering me to do this. Why this may have been significant to me I do not know but the sense of fear was palpable. I understood in the moment of waking why people are corralled into doing that which is not to their taste by pressures of the world. How to enshrine that lesson into a more emotionally-felt, permanent sensation that stayed in my mind, giving better understanding of why people in some situations act as they do?

If people understood more of what life was like in London in the blitz or the Black Death, we would be better equipped to deal emotionally with Covid.

It would be helpful if people take on board the idea that there is a threshold point in systems of belief, a point at which what holds good up to that point, no longer holds good thereafter. Fontenelle was treated in many ways as a vapid dilettante devoid of ambition beyond shining with wit in French pre-revolutionary drawing rooms but why consider his philosophy largely to the exclusion his lifestyle; he fought hard to get himself into the Académie Française but when he achieved his primary ambitions, he saw the key point – he knew where to stop.

People do think up novel ways of training. By way of an outré example, Goldie Hawn, the actress, said that her husband’s punishment for his son was to, “…shoot up his car and dent it up, and ride around in it for the rest of his existence.” Also – this has bearings on reflection – a penalty for misbehaviour of her children was to be sent to a corner, and to sit there with the instruction to reflect there on what they had done wrong.

What could be done constructive apart from considering morality as a factor in education?

Much as nowadays we talk of emotional intelligence, a ‘Filboid’ drug is yet to be rolled out – though no doubt it exists if by another name and purpose – allowing a seeker after truth to absorb useful lessons in life by undergoing a form of self-improvement through a sensation of a harsh reality, one that as a result imprints itself in memory. How could it be done? Here are suggestions and there could be countless others:

This could be in an induced trance under laboratory conditions allowing pupils get genuine experience at first hand of a wholesome shock at a gamut of filmed situations. This would be a dummy run at scenarios best avoided.[2]

If this idea is taken up there may be alternative ways to achieve the same purpose.

An inter-disciplinary course of hypnosis to implant in the mind suitable scare stories, for instance from dieticians, advising against indigestible foodstuff, so as to induce nightmares, topped up perhaps with a medical potion to bring added sensitivity to the body. This, after careful testing, might impart a realistic early-warning lesson?

An assumption thus far in this piece is that wisdom is freighted with an emotional charge and comes of experience but there is another sort of wisdom, that of sheer common sense, with a flavouring of realism.

How to study a situation and how to disentangle from often complex problems the cardinal aspects of them and then act without going by the book, which so often does not meet the exigencies of the case? The consideration of why people act as they do could be quite a study. In the example of Fontenelle (above) his motives could be examined. All was not as it appeared. King Boris of Bulgaria was considered by Churchill to be a ‘weak and vacillating cypher’ but Goebbels said he was a ‘cunning fox’. Who was right? Was not the very fact that King Boris, whose actions saved the lives of countless thousands of Jews in WW2, left as little evidence of his true intention as possible an indication that evaluations of contemporaries who did not work out for themselves what was afoot are suspect?

Can lateral thinking be taught? It comes down to a state of mind which can be fostered

How to train people to think round corners; how to encourage them to think out of the box?

A key question to be posed in hypothetical situations is ‘What are the critical parameters of a situation’? What lies beneath the paintwork and the cosmetics? How to distinguish between ‘the use of a principle and the abuse of it’? Hypocritical prating being commonplace, how to train people to be on the watch for it? A normative question to ask may be ‘where are the elephants in the room?’ Attention to actualities, to motivations, and the stance of being flexed to detect cant goes to cultivating an attitude attuned to sensible goals. Brains’ Trust debates as to means and ends more than a regurgitation of received wisdom and facts, might be a way forward. Reflection helps one think clearly for oneself.

People should be encouraged to think for themselves not being coached. It can become a habit to ask the right question.

As mentioned, a corpus of received wisdom can get in the way of thinking out a solution that is not text book. Facts can clutter the impetus for fresh thinking. There exists an awareness that a collation of cold facts, put together in a presentable array, rarely enough furnishes all the best solutions.

The ‘S’ level paper, taken with ‘A’ levels, was designed to test the ability of a student to think for himself. The right result matters and sometimes the intelligent thing to do is an apparently unintelligent thing.

Example: A student does not wish to spend several afternoons of a summer term when he could be studying for ‘A’ levels playing compulsory school cricket…so he starts playing cricket years beforehand so badly that he is not selected for any team and is detailed off to some subsidiary but less well policed sport and then, come the time of his ‘A’ levels, he is freed up to study during the time that his compeers fritter away time with willow and leather. Or, a pupil is not good at a subject but needs to pass an ‘O’ level in it. As with as archer who uses several arrows in his quiver to hit a bullseye, he has several shots at the target, taking the exam not just on one examination board but on several boards.

It is not easy to thumb a nose at ‘the wisdom of the ages’ till one sees how often that wisdom is not a fixed point, and there are wise ways to accomplish unwise ends. Clear vision counts. Practice with experiment and reflection makes (almost) perfect. Much is revealed if one does so.

The quest of thinking completely afresh properly is far from easy and no one is likely to embark on it with a serious intent until it is seen why this might be a really useful thing to do.

When there is a will, there is usually a way. Therefore, cultivate the will.